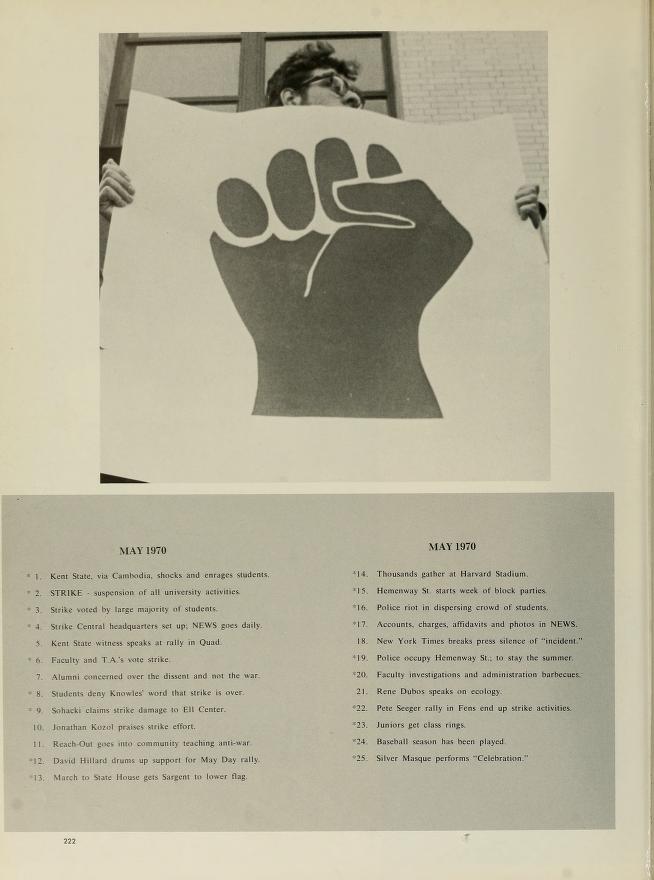

Strikes and Riots: May 1970

April 30-May 4

Only fifteen days after the April 15 protests, President Nixon announced the United States had invaded Cambodia. Leftist student groups began to call for boycotts and strikes, citing expansion in Southeast Asia, the government’s treatment of political dissidents like the Black Panthers, and higher education ROTC programs and defense research. A new wave of campus demonstrations ensued, among which was a protest at Kent State University on Monday, May 4. The day ended in the Ohio National Guard shooting and killing four unarmed students. Fear and outrage swept campuses nationwide. Senator Edward M. Kennedy likened the events to those at My Lai, while the President of the National Student Association, Charles S. Palmer, called the tragedy “the ‘massacre’ of our time" (Storin 1970).

Emergency administrative, faculty, and student government meetings were held around the country to prepare for student protests. By midnight on May 5, around 100 colleges and universities had filed official plans to strike with the newly opened National Strike Information Center (NSIC) at Brandeis University. Over the course of the next few weeks, the NSIC would report strikes at hundreds of colleges and universities across the country, 60 of which were closed for at least several weeks. This number seemed to reach its peak around May 8, when NSIC reported activity at 356 campuses. In addition to undergraduates, a number of students at American high schools and graduate schools voted to participate in strikes and protests. The University of Washington estimates that, based on NSIC reports, protests or strikes were held at 883 schools during this period and involved over one million students (Miller n.d.)

May 5-7

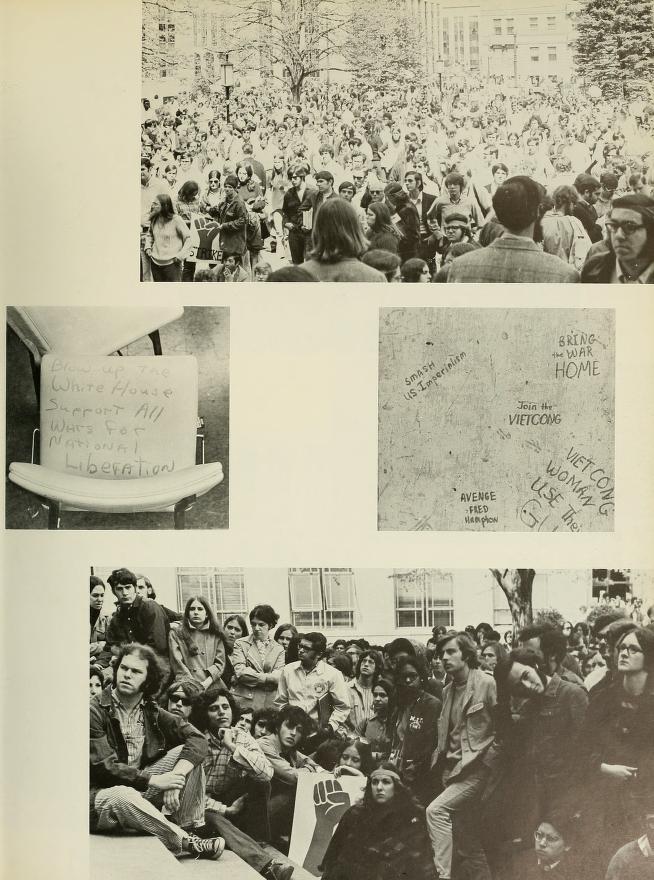

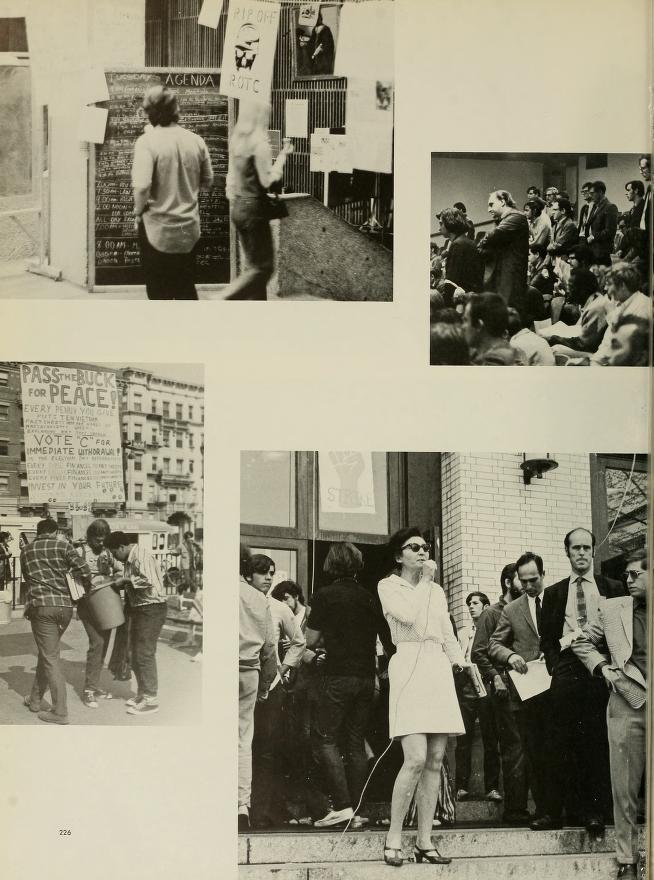

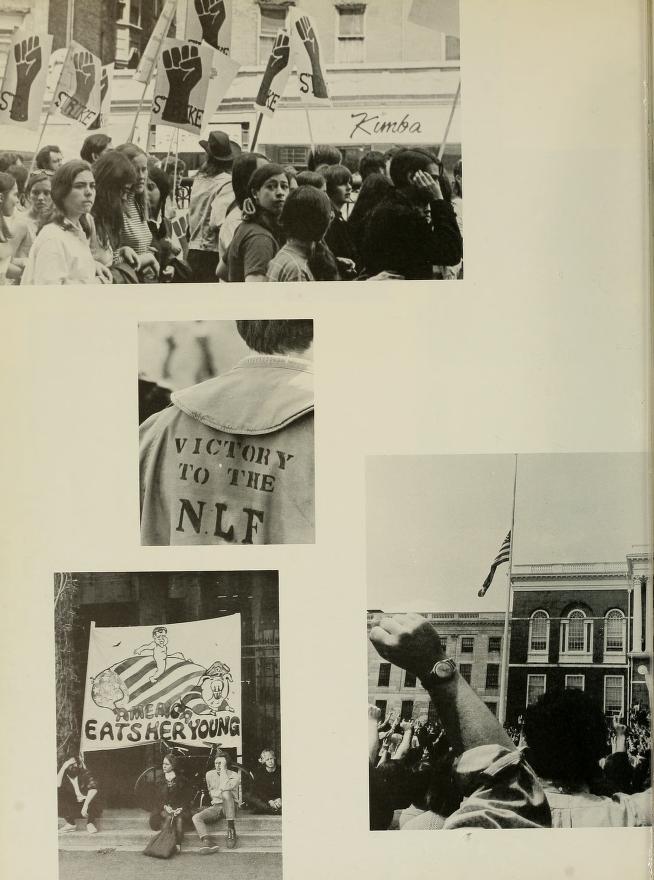

By Wednesday, nearly all colleges in the Boston area and most in Massachusetts had voted to strike. At Northeastern, students had voted 4,619 to 1,529 in favor of boycotting classes. As at many local universities, this decision was largely supported by the student government and faculty, though more conservative administrators and faculty members expressed concern. For the rest of the week, Boston area universities deliberated about how to handle classes and final examinations. More than ever, it seemed that students had public opinion on their side. A number of local religious, legal, and political leaders joined students in denouncing the recent national events. The State Senate passed a resolution condemning the situation in Cambodia, and Representative H. James Shea drafted a new bill to challenge the War’s constitutionality. On Thursday, May 7, Northeastern’s faculty and administrators voted to discontinue normal academic activities indefinitely, allowing faculty to decide whether to participate in the strike or hold classes with voluntary student attendance.

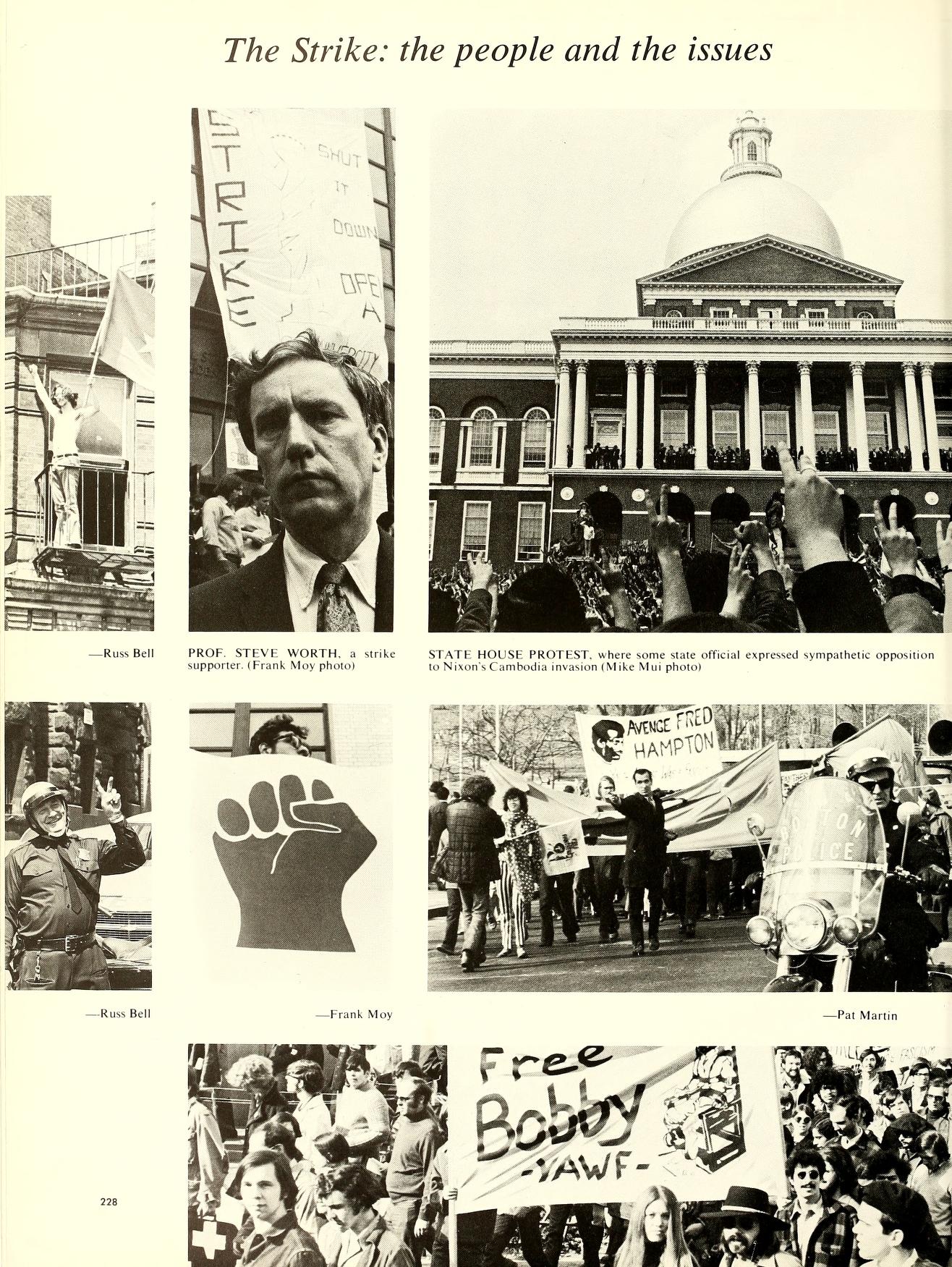

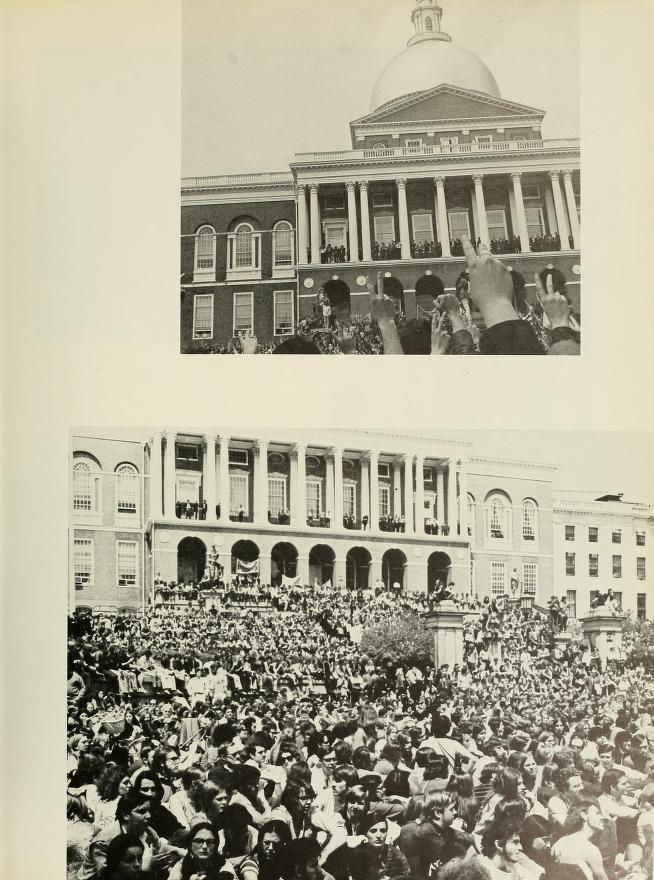

While administrators deliberated, students demonstrated, canvassed, and occupied spaces for their cause. The day after Kent State, 3,000 Northeastern students joined an estimated 20,000-25,000 at the State House for a rally organized by the Student Mobilization Committee. The rally started around noon and lasted two and a half hours, including speeches from local politicians and activists condemning the War and political hypocrisy. During the nonviolent event, protestors successfully urged Governor Sargent to lower the flag to half mast to honor the four student victims. The rally was followed by a smaller, largely peaceful protest at the Commonwealth Armory.

May 5-7

By Wednesday, nearly all colleges in the Boston area and most in Massachusetts had voted to strike. At Northeastern, students had voted 4,619 to 1,529 in favor of boycotting classes. As at many local universities, this decision was largely supported by the student government and faculty, though more conservative administrators and faculty members expressed concern. For the rest of the week, Boston area universities deliberated about how to handle classes and final examinations. More than ever, it seemed that students had public opinion on their side. A number of local religious, legal, and political leaders joined students in denouncing the recent national events. The State Senate passed a resolution condemning the situation in Cambodia, and Representative H. James Shea drafted a new bill to challenge the War’s constitutionality. On Thursday, May 7, Northeastern’s faculty and administrators voted to discontinue normal academic activities indefinitely, allowing faculty to decide whether to participate in the strike or hold classes with voluntary student attendance.

While administrators deliberated, students demonstrated, canvassed, and occupied spaces for their cause. The day after Kent State, 3,000 Northeastern students joined an estimated 20,000-25,000 at the State House for a rally organized by the Student Mobilization Committee. The rally started around noon and lasted two and a half hours, including speeches from local politicians and activists condemning the War and political hypocrisy. During the nonviolent event, protestors successfully urged Governor Sargent to lower the flag to half mast to honor the four student victims. The rally was followed by a smaller, largely peaceful protest at the Commonwealth Armory.

May 8-9

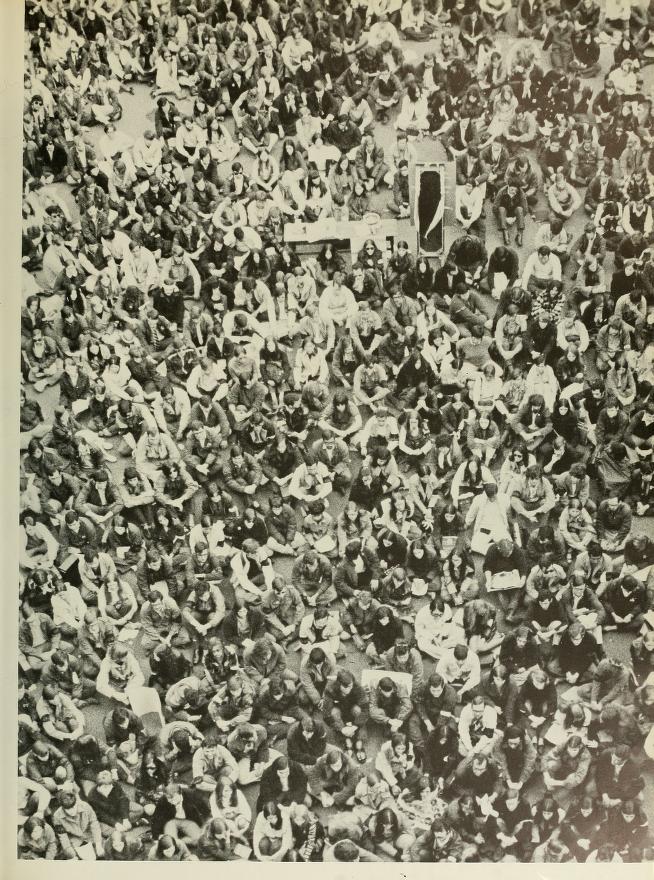

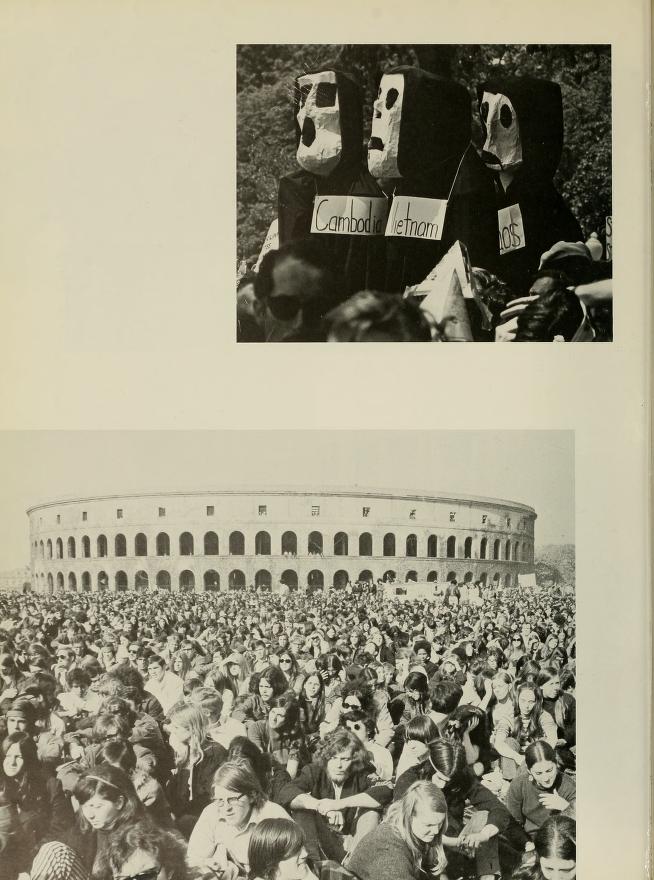

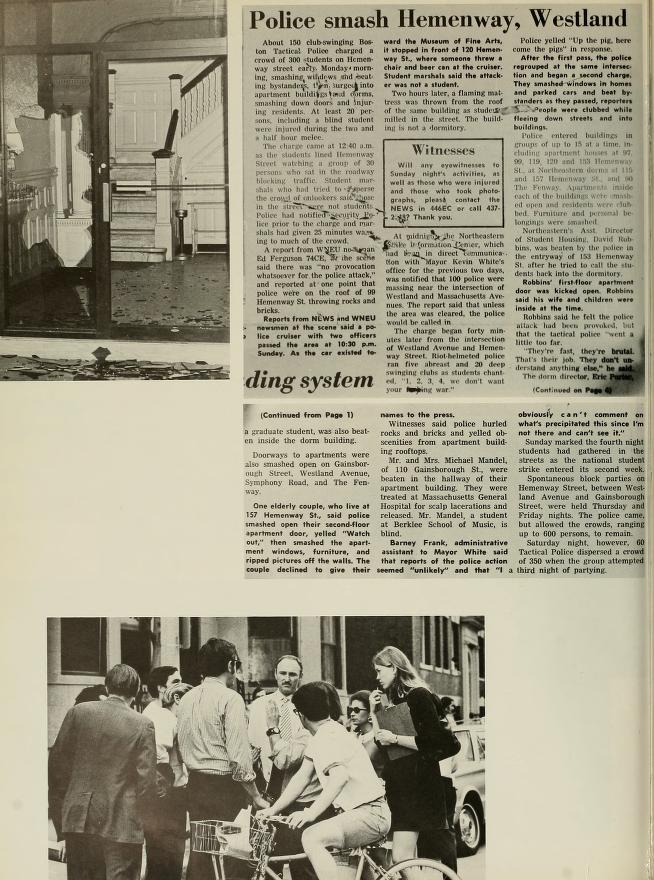

On Thursday, students from a number of colleges focused on encouraging citizens who opposed the War to write to Washington, setting up telegram writing booths, distributing flyers on the street and MBTA, and canvassing neighborhoods. That night Northeastern saw its largest on-campus protest since the strike began, when about 2,000 students marched peacefully on the ROTC building and burned a coffin symbolizing American imperialism. New local action coalitions were formed, and small rallies, picket lines, and marches on various campuses occurred throughout the rest of the week. A peaceful rally drew thousands to a field near Harvard Stadium on Friday. Northeastern students welcomed the weekend with a series of block parties on Thursday and Friday night on Hemenway Street.

Meanwhile in Washington, the President’s promise that troops would leave Cambodia by June 30 failed to mollify plans for protest by the New Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam (“New Mobe”). The Federal Court had restricted protesting near the White House on May 5, but fearing further retaliation, the Administration entered negotiations with New Mobe to grant a permit for a rally on Saturday, May 9. The Harvard Peace Action Strike Committee organized buses for about five hundred students -- representing nearly every school in the area -- to travel to Washington to picket Henry Kissinger’s house and join about 100,000 others in the Saturday protest.

Back in Massachusetts, H. James Shea would die from a self-inflicted gunshot wound just after midnight on Saturday, at 30 years old. Reports cited his death as a result of political pressure and a sense of hopelessness with the situation in Southeast Asia. The death of a young, progressive political leader resonated with Boston area students, many of whom had seen his last public speech at Tuesday’s rally at the State House.

May 10-11

Incidents of violence and police brutality had occurred at several local universities during that first week, but strike activities at Northeastern had been largely peaceful. This would change in the early hours of Monday, May 11, in an incident which retrospectives have framed as the climax of the University’s anti-War movement.

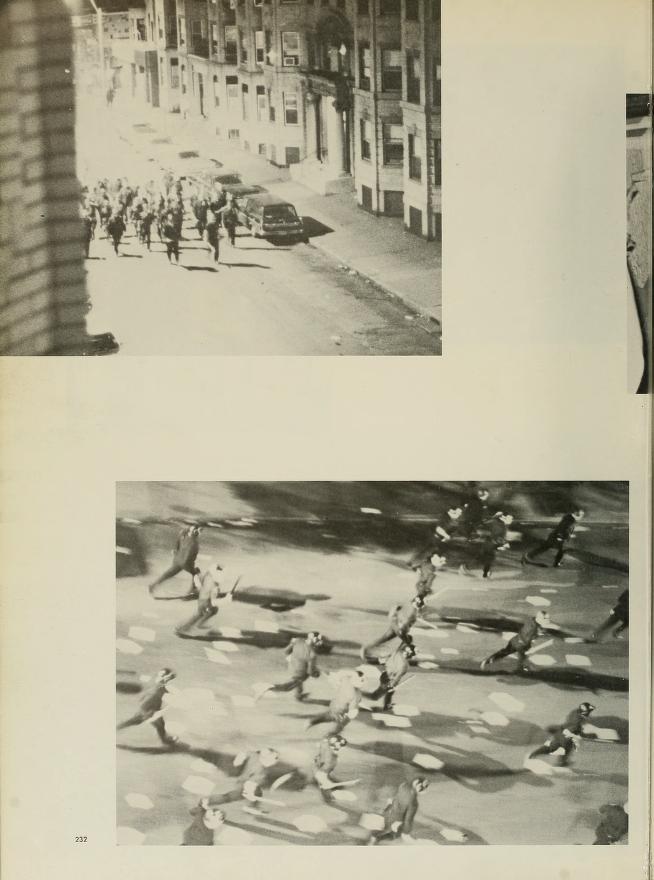

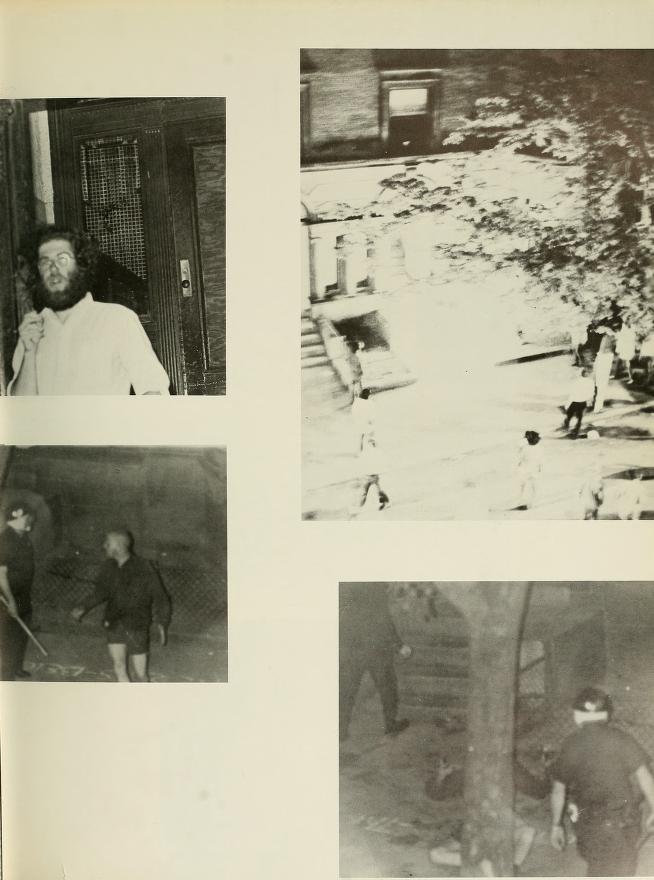

Late in the evening of May 10, Boston police reported receiving noise complaints for activity around Hemenway Street. Policemen gathered near Massachusetts Avenue and Westland Avenue, announcing that police would forcibly clear students from the area if they did not leave. The first charge began around 12:40 a.m. Students and bystanders reported 100-150 riot-helmeted, club-swinging Tactical Police ran in from the intersection of Westland Avenue and Hemenway Street towards about 300 people. After the first pass, they regrouped and began a second charge. Witnesses recalled police smashing windows and forcibly entering dormitories and other residential buildings; clubbing people at random on the streets and in their rooms; destroying furniture and other belongings; and hurling rocks, bricks, and other debris at students from rooftops. By the end of the evening at least 20 people were injured, many in their own homes. Michael Mandel, a blind student at the Berklee School of Music, was beaten with his wife while trying to enter their apartment. David Robbins, Northeastern’s Assistant Director of Housing, was beaten while attempting to usher students into their dormitories. Some waited for hours in their homes until it was safe enough to seek medical attention for their injuries.

The event, later referred to as the Hemenway Street incident or riot, was a reminder to students and local residents of how opposing authority meant risking brutality. The Northeastern News -- running daily since the strike began -- covered the riot extensively and collected photographs and eyewitness testimonies of the events. According to the 1971 Cauldron, the incident was largely ignored by larger media outlets, until around May 15 when the New York Times acknowledged the event as a police riot. The article quoted one Boston official claiming it was “the worst case of police overreaction” in recent Boston history (Lukas 1970).

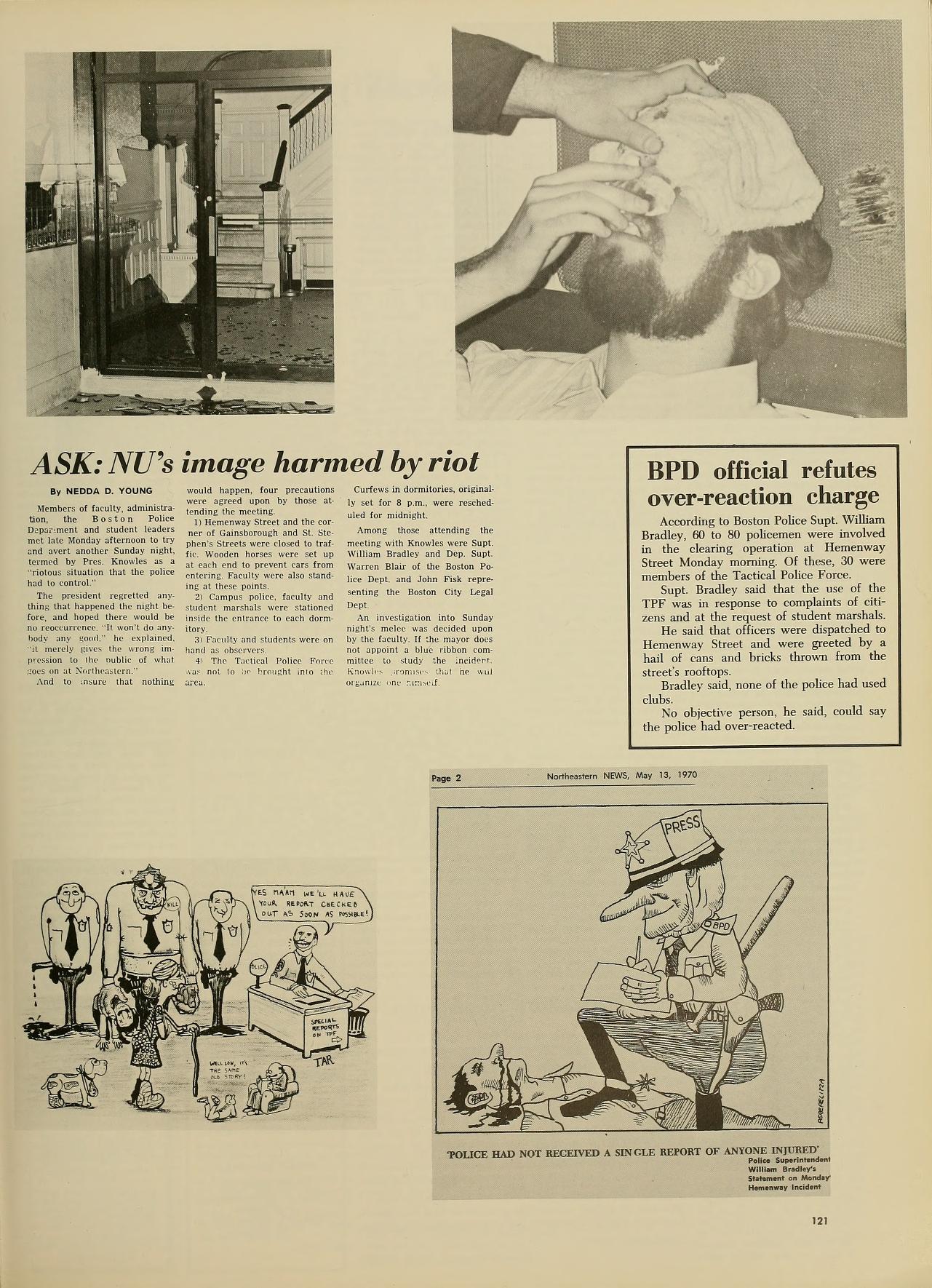

Members of the administration, faculty, and Boston Police Department met in the late afternoon of May 11 to discuss the incident. Boston Police Supt. William Bradley reported that only 60-80 policemen -- including 30 Tactical Police Force members -- were present, and that none had used clubs. Reports quoted the Superintendent as stating, “No objective person could say the police had over-reacted" (Cauldron 1972, 121). President Knowles was cited as calling the event “a riotous situation that the police had to control”, but promised to conduct an investigation into the incident if the mayor did not (Young 1970). Faculty members expressed concern for future student safety, and volunteered to help keep watch at Hemenway Street and ROTC headquarters at the Greenleaf Building. To reduce future conflict, meeting attendees agreed on new area precautions, including closing Hemenway Street to traffic; stationing faculty, student marshalls, and campus police in dormitories; and excluding Tactical Police from the area.

May 12-15

Over the next few days, students claimed President Knowles had told the press that normal activities had resumed on campus. On Wednesday, May 13, 50 students marched to the President’s office, insisting the strike was still ongoing and the President was subverting student efforts by spreading misinformation. Nevertheless, Northeastern’s strike officially ended two days later, on May 15. Exhausted, students left for summer, and the campus fervor for protest began to wane.