Rising Conflict: January-April 1970

January

2023-05-25T16:37:42Z

A

CoreFile

neu:m04337372

{"datastreams":{"RELS-EXT":{"dsLabel":"Fedora Object-to-Object Relationship Metadata","dsVersionID":"RELS-EXT.0","dsCreateDate":"2018-05-16T20:07:05Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"application/rdf+xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"X","dsSize":420,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:m04337372+RELS-EXT+RELS-EXT.0","dsLocationType":null,"dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"rightsMetadata":{"dsLabel":null,"dsVersionID":"rightsMetadata.2","dsCreateDate":"2018-08-20T17:01:15Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"M","dsSize":713,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:m04337372+rightsMetadata+rightsMetadata.2","dsLocationType":"INTERNAL_ID","dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"DC":{"dsLabel":"Dublin Core Record for this object","dsVersionID":"DC.11","dsCreateDate":"2023-05-25T16:37:42Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":"http://www.openarchives.org/OAI/2.0/oai_dc/","dsControlGroup":"X","dsSize":2599,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:m04337372+DC+DC.11","dsLocationType":null,"dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"properties":{"dsLabel":null,"dsVersionID":"properties.3","dsCreateDate":"2018-05-16T20:07:25Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"M","dsSize":712,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:m04337372+properties+properties.3","dsLocationType":"INTERNAL_ID","dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"mods":{"dsLabel":null,"dsVersionID":"mods.8","dsCreateDate":"2023-05-25T16:37:41Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"M","dsSize":5105,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:m04337372+mods+mods.8","dsLocationType":"INTERNAL_ID","dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"}},"objLabel":null,"objOwnerId":"fedoraAdmin","objModels":["info:fedora/fedora-system:FedoraObject-3.0","info:fedora/afmodel:CoreFile"],"objCreateDate":"2018-05-16T20:07:05Z","objLastModDate":"2023-05-25T16:37:42Z","objDissIndexViewURL":"http://localhost:8080/fedora/objects/neu%3Am04337372/methods/fedora-system%3A3/viewMethodIndex","objItemIndexViewURL":"http://localhost:8080/fedora/objects/neu%3Am04337372/methods/fedora-system%3A3/viewItemIndex","objState":"A"}

northeastern:drs:repository:staff

northeastern:drs:library:archives

public

000000000

neu:6012

neu:6012

000000000

000000000

/downloads/neu:m0433739m?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m0433739m?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m0433739m?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m0433739m?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m0433739m?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

/downloads/neu:m0433739m?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m0433739m?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m0433739m?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m0433739m?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m0433739m?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

ImageMasterFile

ImageMasterFile

neu:6012

000000000

/downloads/neu:m0433739m?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m0433739m?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m0433739m?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m0433739m?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m0433739m?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

ImageMasterFile

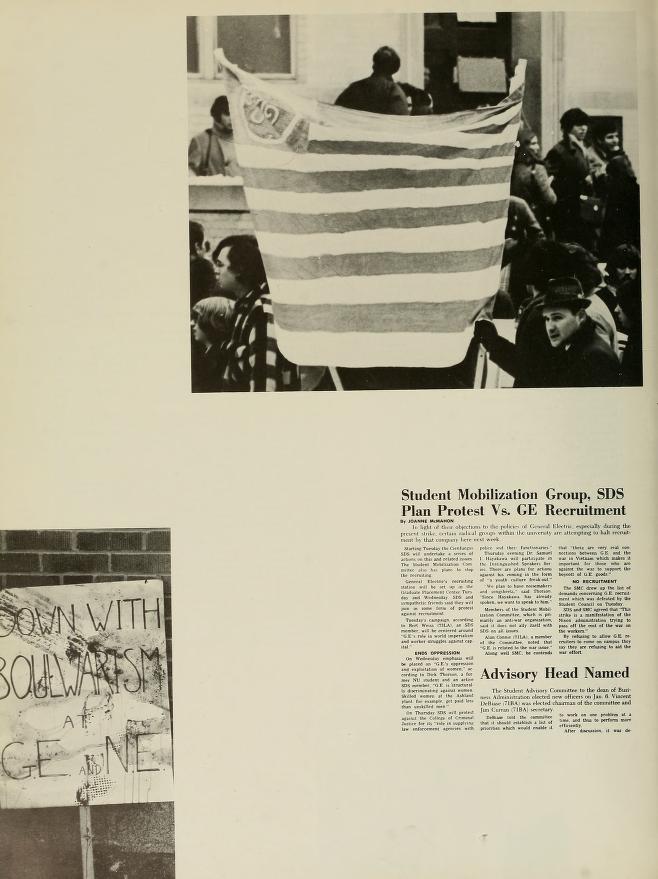

African American and white female students at an anti-war protest

African American and white female students at an anti-war protest

African American and white female students at an anti-war protest

African American and white female students at an anti-war protest

Image appeared in 1970 Cauldron yearbook.

photographs

1970

1970

Selected resources in this collection were acquired through transferals from Northeastern's Office of University Photography, Jet Commercial Photographers, Northeastern University publications, unprocessed archival collections and other contract photographers.

Collection finding aid: https://archivesspace.library.northeastern.edu/repositories/2/resources/761

Northeastern University (Boston, Mass.)

Northeastern University (Boston, Mass.)

Northeastern University (Boston, Mass.)

Northeastern University (Boston, Mass.)

Massachusetts

Boston

Massachusetts

Boston

United States

Massachusetts

Boston

College students

Demonstrations

Vietnam War, 1961-1975

Protest movements

College students

Massachusetts

Boston

Demonstrations

United States

Vietnam War, 1961-1975

Protest movements

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20284329

A030317

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20284329

College students

Demonstrations

Vietnam War, 1961-1975

Protest movements

African American and white female students at an anti-war protest

Northeastern University Photograph collection (A103)

African American and white female students at an anti-war protest

african american and white female students at an antiwar protest

1970/01/01

approximate

African American and white female students at an anti-war protest

1970

Northeastern University (Boston, Mass.)

College students Massachusetts Boston

Demonstrations Massachusetts Boston

Vietnam War, 1961-1975 Protest movements United States

info:fedora/afmodel:CoreFile

info:fedora/neu:6012

2023-05-25T17:20:30.409Z

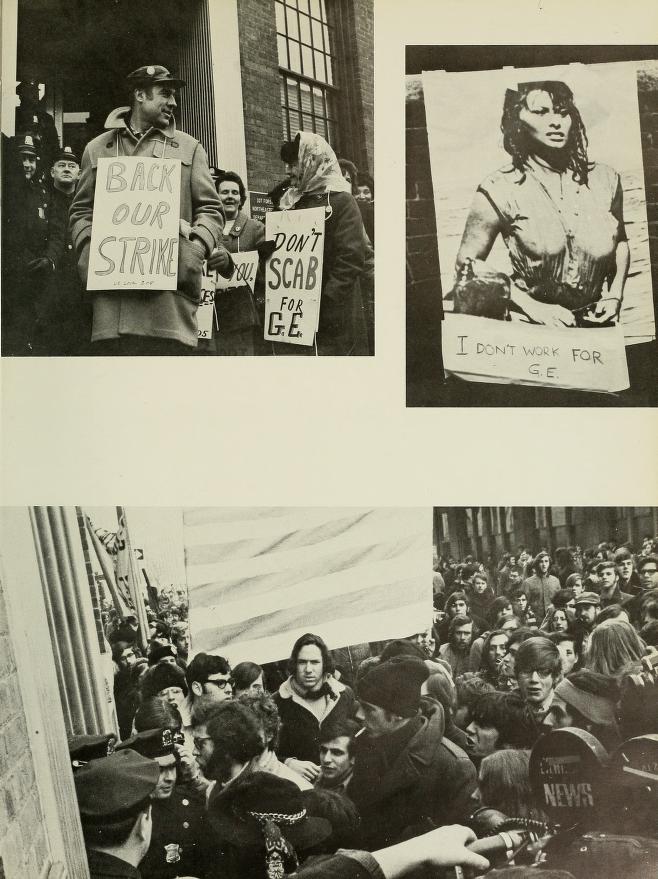

The University attempted to go to court and obtain an injunction against six student protest leaders in an attempt to disrupt demonstration plans. In a move that showed solidarity with the SDS, the Student Council held an emergency meeting to stop the injunction and presented a statement to Knowles and the executive committee. Council President Robert Weisman, Vice-President Frank Gerry, and Secretary Mike Putnam criticized the administration for neglecting to consult the elected student body, thereby violating a prior agreement with the Council. The statement asserted that by seeking an injunction, the administration had “placed the university in a position in which the likelihood of violent confrontation may well now be inevitable" (Dorfsman 1969). Ultimately the order was served against only two of the six students originally targeted.

On January 26, demonstrators voted to hold a non-obstructive picket line at 9:45 a.m. the following morning at the recruitment site. The Boston Globe reported more than 225 picketers participated, consisting of mostly SDS and SMC students but also about a dozen United Electrical, Radio, and Machine Workers from the GE Ashland plant. Protestors were opposed by an equal number of counter-demonstrators across the street, who cheered students who crossed the picket line. Interviewee turnout was lower than expected and resulted in the cancellation of a planned second day of interviews.

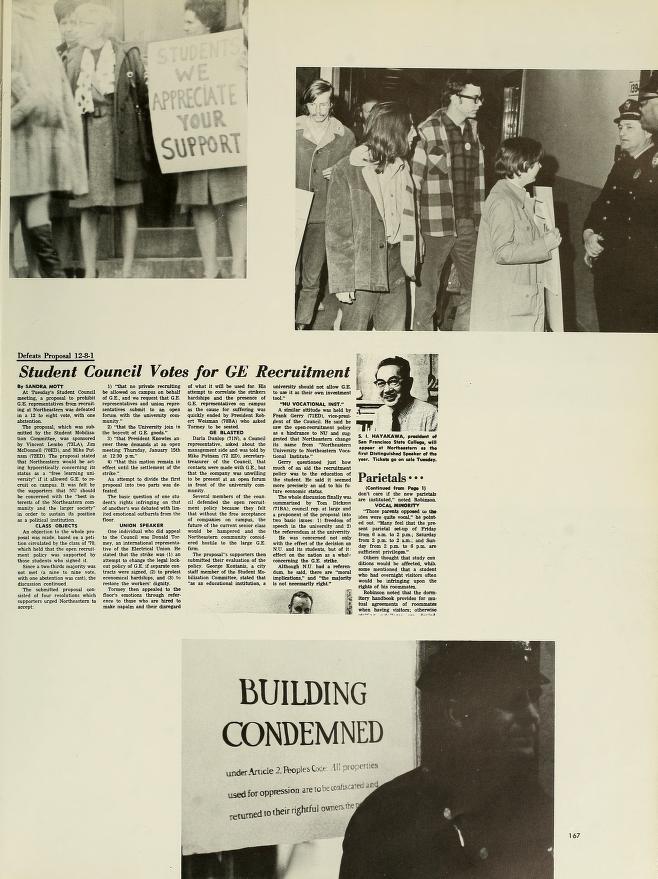

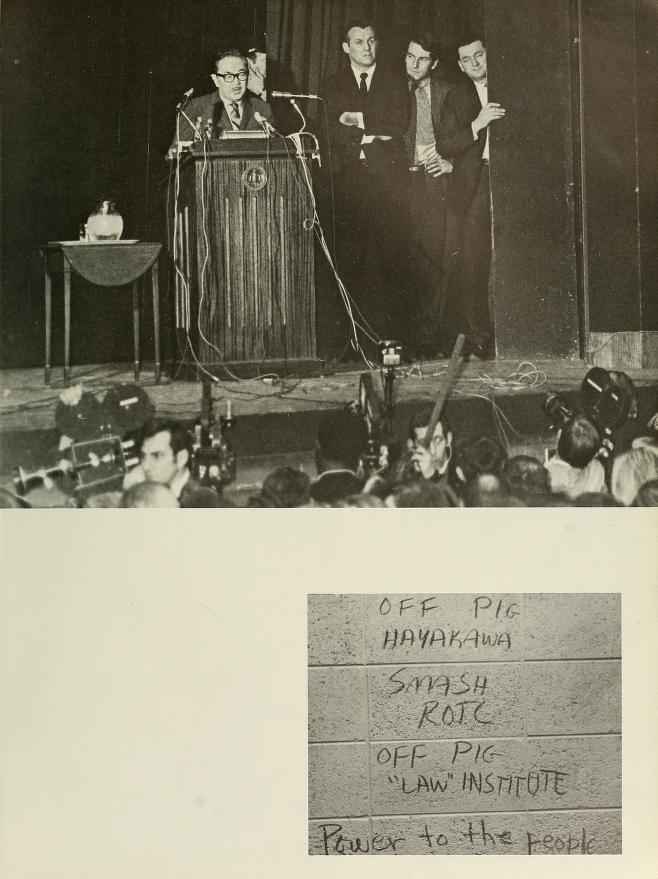

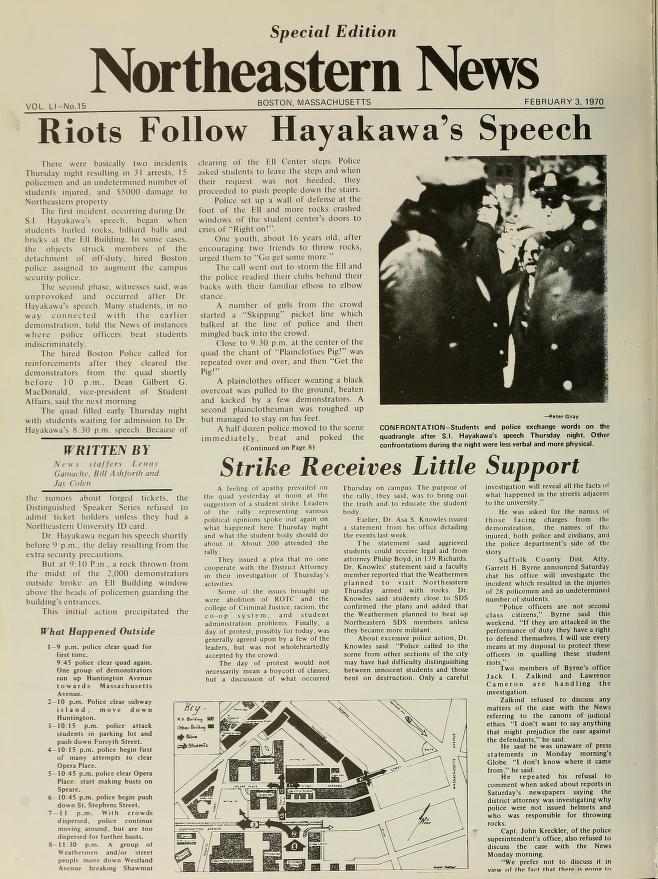

Only two days later, a more hostile incident would leave Northeastern students questioning the role and risk of violence in the growing peace movement. The student-sponsored Distinguished Speakers Series, designed to facilitate dialog between progressives and conservatives, had invited S. I. Hayakawa to speak on campus on January 29. Boosted by the momentum of the GE demonstration, anti-War sympathizers were eager to challenge the controversial President of San Francisco State University, who had previously demonstrated hostility towards student protesters, other SDS chapters, and the Black Panthers. The Student Council and SDS agreed on silent bubble blowing during the event as a peaceful means of protest, while Knowles anticipated a more boisterous demonstration and sought a heightened police presence.

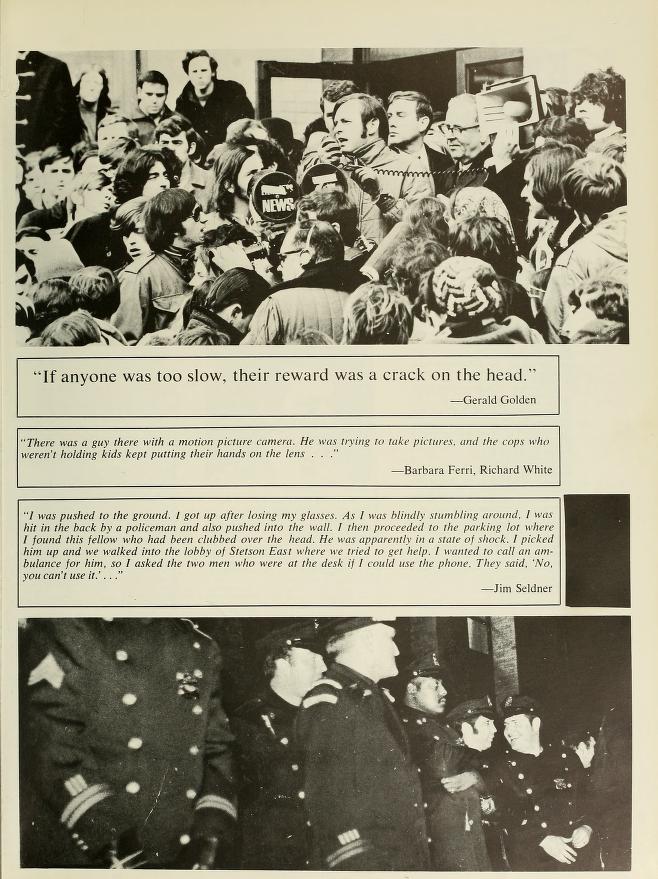

Students gathered on the quad on the day of the event. When rocks were thrown, police reacted violently. Witnesses state students were beaten and dragged across the quad, with police pursuing them down Huntington Avenue and St. Stephen’s Street. Some took refuge in the women’s dorms or St. Anne’s Church. Five students required hospitalization, and several dozen were bailed out of jail with the help of faculty. The 1973 Cauldron summarized: “Whether the carnage and chaos in the Quad was due to police brutality, left-wing subversive agitators, or frayed human nerves on both sides, no one will ever know for certain. But when the dust cleared 31 students had been arrested; 15 policemen and an unknown number of students had been injured by flying rocks, bottles, bricks, and fists; and the campus had suffered $5,000 in damages" (65). Nineteen students would end up being charged, most of whom were eventually acquitted.

The following day, students again gathered on the Quad and demanded a response from Knowles. The President consented to granting legal counsel and medical care for students, and promised to conduct an investigation into the incident under pressure from the Student Council. A number of students called for strike. Those in favor cited the administration’s complicity in the Hayakawa violence, continued resistance to the anti-ROTC and anti-War movement, enduring institutional racism, and other sustained efforts to subvert student power and social reform. Ultimately, academic activities continued as normal, despite minor protests and bomb scares over the next few months. Students would have new reason to strike later that spring.

2023-05-24T14:43:23Z

A

CoreFile

neu:m0432s32t

{"datastreams":{"RELS-EXT":{"dsLabel":"Fedora Object-to-Object Relationship Metadata","dsVersionID":"RELS-EXT.0","dsCreateDate":"2018-05-16T17:31:11Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"application/rdf+xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"X","dsSize":420,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:m0432s32t+RELS-EXT+RELS-EXT.0","dsLocationType":null,"dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"rightsMetadata":{"dsLabel":null,"dsVersionID":"rightsMetadata.2","dsCreateDate":"2018-08-20T16:56:56Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"M","dsSize":713,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:m0432s32t+rightsMetadata+rightsMetadata.2","dsLocationType":"INTERNAL_ID","dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"DC":{"dsLabel":"Dublin Core Record for this object","dsVersionID":"DC.11","dsCreateDate":"2023-05-24T14:43:23Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":"http://www.openarchives.org/OAI/2.0/oai_dc/","dsControlGroup":"X","dsSize":2299,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:m0432s32t+DC+DC.11","dsLocationType":null,"dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"properties":{"dsLabel":null,"dsVersionID":"properties.3","dsCreateDate":"2018-05-16T17:31:38Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"M","dsSize":712,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:m0432s32t+properties+properties.3","dsLocationType":"INTERNAL_ID","dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"mods":{"dsLabel":null,"dsVersionID":"mods.8","dsCreateDate":"2023-05-24T14:43:22Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"M","dsSize":4913,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:m0432s32t+mods+mods.8","dsLocationType":"INTERNAL_ID","dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"}},"objLabel":null,"objOwnerId":"fedoraAdmin","objModels":["info:fedora/fedora-system:FedoraObject-3.0","info:fedora/afmodel:CoreFile"],"objCreateDate":"2018-05-16T17:31:11Z","objLastModDate":"2023-05-24T14:43:23Z","objDissIndexViewURL":"http://localhost:8080/fedora/objects/neu%3Am0432s32t/methods/fedora-system%3A3/viewMethodIndex","objItemIndexViewURL":"http://localhost:8080/fedora/objects/neu%3Am0432s32t/methods/fedora-system%3A3/viewItemIndex","objState":"A"}

northeastern:drs:repository:staff

northeastern:drs:library:archives

public

000000000

neu:6012

neu:6012

000000000

000000000

/downloads/neu:m0432s34c?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m0432s34c?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m0432s34c?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m0432s34c?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m0432s34c?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

/downloads/neu:m0432s34c?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m0432s34c?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m0432s34c?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m0432s34c?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m0432s34c?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

ImageMasterFile

ImageMasterFile

neu:6012

000000000

/downloads/neu:m0432s34c?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m0432s34c?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m0432s34c?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m0432s34c?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m0432s34c?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

ImageMasterFile

Emory being dragged off quad

Emory being dragged off quad

Emory being dragged off quad

Emory being dragged off quad

photographs

1970

1970

Selected resources in this collection were acquired through transferals from Northeastern's Office of University Photography, Jet Commercial Photographers, Northeastern University publications, unprocessed archival collections and other contract photographers.

Collection finding aid: https://archivesspace.library.northeastern.edu/repositories/2/resources/761

Northeastern University (Boston, Mass.)

Northeastern University (Boston, Mass.)

Northeastern University (Boston, Mass.)

Northeastern University (Boston, Mass.)

Massachusetts

Boston

United States

Massachusetts

Boston

College students

Vietnam War, 1961-1975

Protest movements

College students

United States

Vietnam War, 1961-1975

Protest movements

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20283889

A029262

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20283889

College students

Vietnam War, 1961-1975

Protest movements

Emory being dragged off quad

Northeastern University Photograph collection (A103)

Series 15: Student Life. Subseries: Protests > Vietnam War

Emory being dragged off quad

emory being dragged off quad

1970/01/01

Emory being dragged off quad

1970

Northeastern University (Boston, Mass.)

College students Massachusetts Boston

Vietnam War, 1961-1975 Protest movements United States

info:fedora/afmodel:CoreFile

info:fedora/neu:6012

2023-05-24T14:43:23.804Z

2023-05-24T14:48:18Z

A

CoreFile

neu:m0432s597

{"datastreams":{"RELS-EXT":{"dsLabel":"Fedora Object-to-Object Relationship Metadata","dsVersionID":"RELS-EXT.0","dsCreateDate":"2018-05-16T17:34:45Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"application/rdf+xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"X","dsSize":420,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:m0432s597+RELS-EXT+RELS-EXT.0","dsLocationType":null,"dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"rightsMetadata":{"dsLabel":null,"dsVersionID":"rightsMetadata.2","dsCreateDate":"2018-08-20T16:57:10Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"M","dsSize":713,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:m0432s597+rightsMetadata+rightsMetadata.2","dsLocationType":"INTERNAL_ID","dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"DC":{"dsLabel":"Dublin Core Record for this object","dsVersionID":"DC.11","dsCreateDate":"2023-05-24T14:48:18Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":"http://www.openarchives.org/OAI/2.0/oai_dc/","dsControlGroup":"X","dsSize":2262,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:m0432s597+DC+DC.11","dsLocationType":null,"dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"properties":{"dsLabel":null,"dsVersionID":"properties.3","dsCreateDate":"2018-05-16T17:35:08Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"M","dsSize":711,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:m0432s597+properties+properties.3","dsLocationType":"INTERNAL_ID","dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"mods":{"dsLabel":null,"dsVersionID":"mods.8","dsCreateDate":"2023-05-24T14:48:18Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"M","dsSize":5687,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:m0432s597+mods+mods.8","dsLocationType":"INTERNAL_ID","dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"}},"objLabel":null,"objOwnerId":"fedoraAdmin","objModels":["info:fedora/fedora-system:FedoraObject-3.0","info:fedora/afmodel:CoreFile"],"objCreateDate":"2018-05-16T17:34:45Z","objLastModDate":"2023-05-24T14:48:18Z","objDissIndexViewURL":"http://localhost:8080/fedora/objects/neu%3Am0432s597/methods/fedora-system%3A3/viewMethodIndex","objItemIndexViewURL":"http://localhost:8080/fedora/objects/neu%3Am0432s597/methods/fedora-system%3A3/viewItemIndex","objState":"A"}

northeastern:drs:repository:staff

northeastern:drs:library:archives

public

000000000

neu:6012

neu:6012

000000000

000000000

/downloads/neu:m0432s618?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m0432s618?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m0432s618?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m0432s618?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m0432s618?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

/downloads/neu:m0432s618?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m0432s618?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m0432s618?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m0432s618?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m0432s618?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

ImageMasterFile

ImageMasterFile

neu:6012

000000000

/downloads/neu:m0432s618?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m0432s618?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m0432s618?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m0432s618?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m0432s618?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

ImageMasterFile

Malcolm Emory speaking to a reporter

Malcolm Emory speaking to a reporter

Malcolm Emory speaking to a reporter

Malcolm Emory speaking to a reporter

Caption on back: "NU Voice, Malcolm Emory shows reporters the site of his mistaken arrest on the Quad 20 years ago."

Photographer

Photographer

photographs

1990-07-19

1990-07-19

Selected resources in this collection were acquired through transferals from Northeastern's Office of University Photography, Jet Commercial Photographers, Northeastern University publications, unprocessed archival collections and other contract photographers.

Collection finding aid: https://archivesspace.library.northeastern.edu/repositories/2/resources/761

Northeastern University (Boston, Mass.)

Emory Malcolm

Northeastern University (Boston, Mass.)

Northeastern University (Boston, Mass.)

Northeastern University (Boston, Mass.)

Interviews

Student movements

Interviews

Student movements

Emory Malcolm

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20283898

A029272

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20283898

Interviews

Student movements

Malcolm Emory speaking to a reporter

Northeastern University Photograph collection (A103)

Series 15: Student Life. Subseries: Protests > General

Malcolm Emory speaking to a reporter

malcolm emory speaking to a reporter

1990/07/19

Malcolm Emory speaking to a reporter

1990-07-19

Northeastern University (Boston, Mass.)

Interviews

Student movements

Emory Malcolm

Pike, Glenn

Pike, Glenn

Pike, Glenn

info:fedora/afmodel:CoreFile

info:fedora/neu:6012

2023-05-24T14:48:19.115Z

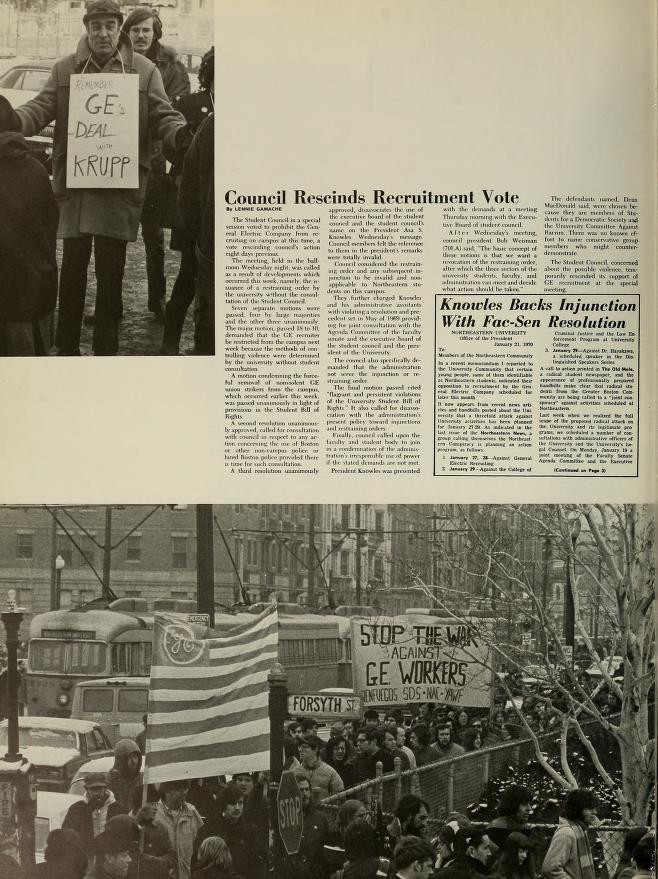

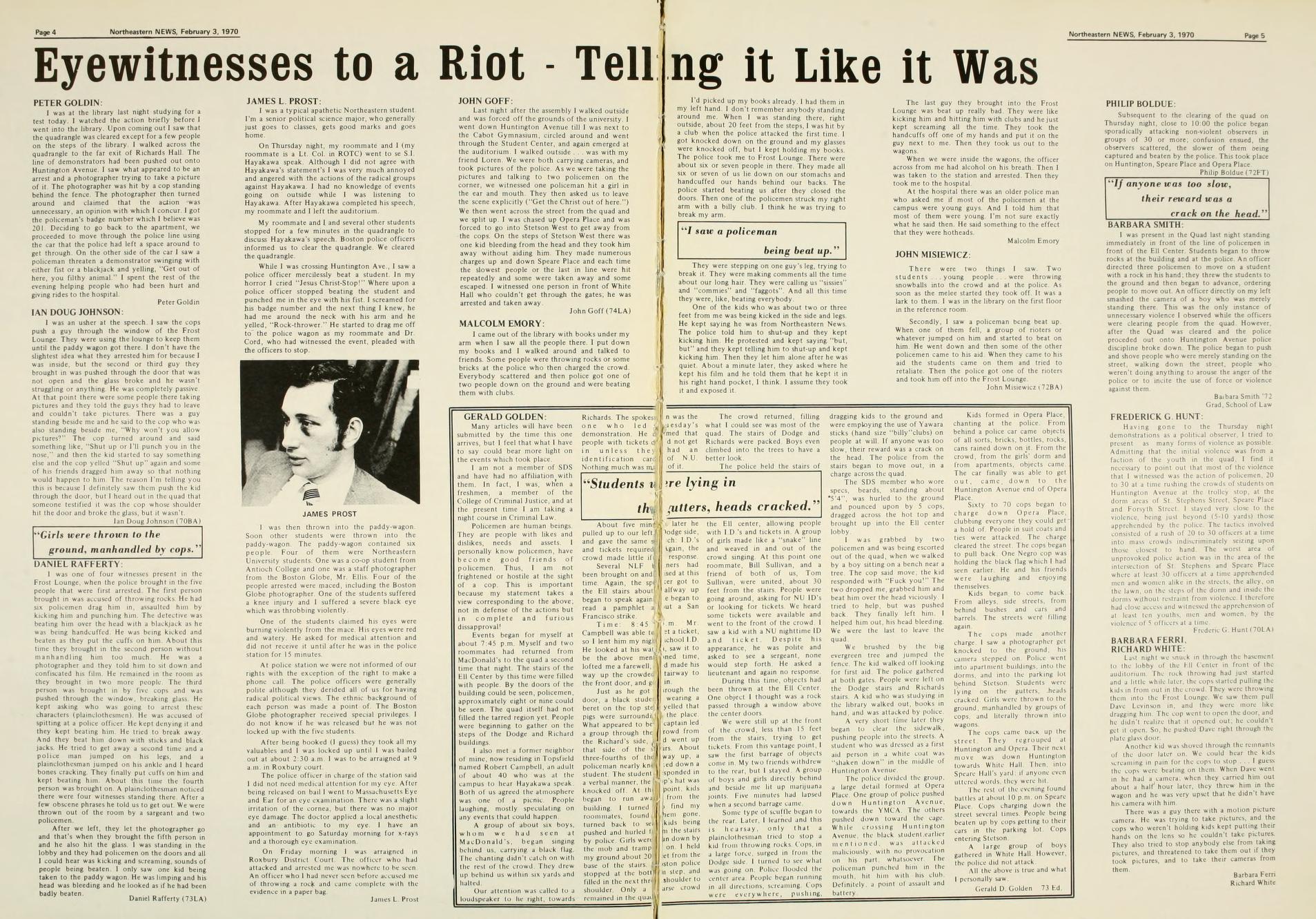

April

As spring progressed, students grew increasingly restless and angry, disillusioned with an enduring War and persistent social injustice despite years of activist organizing. In April, a referendum counting 2,125 Northeastern students found that seventy-four percent favored immediate withdrawal from Vietnam, compared to only ten percent in 1968. On April 15, Northeastern students participated in a third nationwide Moratorium day, joining between 50,000 - 100,000 people on the Boston Common in the largest anti-War gathering in the country. Organized by the SMC and the Vietnam Moratorium Campaign (VMC), the day’s theme was the cost of War in anticipation of tax day, and included marches, vigils, teach-ins, and speeches by national activists and local politicians seeking support for anti-War legislature. Northeastern students held a teach-in at the Quad throughout the morning, followed by an on-campus rally and march to the Common. The press reported an angrier crowd than in the 1969 moratoriums, though the official Boston rally was largely nonviolent. Some controversy arose when Black Panther Douglas Miranda called activists to “kill the pigs”, illustrating a larger, national debate between progressives regarding the role of violence in protest.

After the rally, the November Action Coalition organized a march from the Common to Harvard Square in large part to protest the trial of Bobby Seale in New Haven. When they arrived around 7:30 pm, protestors began smashing windows, lighting fires in trash bins, and breaking into Harvard Yard. Police reacted by readying 2,000 police from every town within 25 miles of Cambridge, and later 2,000 members of the National Guard at the Commonwealth Armory. The Boston Globe called the mobilization “one of the fastest and most expansive police emergency operations in Greater Boston history” to what it deemed “the most extreme disorder in Cambridge history" (Burke and Smith 1970). Witnesses said protesters threw rocks, bricks, and Molotov cocktails at police cars and banks, while police beat people indiscriminately. An estimated 3,000-6,000 people were involved in the incident at its height. By the time the riot ended around midnight, over 200 would need to be treated for injuries by Harvard Health Services.

While it is unclear if any Northeastern students were involved in the incident, the event served as a reminder that tensions were escalating and police were willing to use violence on protestors both on and off campus. Perhaps no other incident during the Vietnam War would illustrate this reality as clearly as the events that took place at Kent State University not three weeks later.

2016-12-08T17:49:50Z

A

CoreFile

neu:cj82nq05k

{"datastreams":{"RELS-EXT":{"dsLabel":"Fedora Object-to-Object Relationship Metadata","dsVersionID":"RELS-EXT.1","dsCreateDate":"2016-10-05T15:54:28Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"application/rdf+xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"X","dsSize":425,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:cj82nq05k+RELS-EXT+RELS-EXT.1","dsLocationType":null,"dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"rightsMetadata":{"dsLabel":null,"dsVersionID":"rightsMetadata.5","dsCreateDate":"2016-12-08T17:49:48Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"M","dsSize":687,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:cj82nq05k+rightsMetadata+rightsMetadata.5","dsLocationType":"INTERNAL_ID","dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"DC":{"dsLabel":"Dublin Core Record for this object","dsVersionID":"DC.6","dsCreateDate":"2016-12-08T17:49:49Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":"http://www.openarchives.org/OAI/2.0/oai_dc/","dsControlGroup":"X","dsSize":731,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:cj82nq05k+DC+DC.6","dsLocationType":null,"dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"properties":{"dsLabel":null,"dsVersionID":"properties.5","dsCreateDate":"2016-10-05T15:56:53Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"M","dsSize":733,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:cj82nq05k+properties+properties.5","dsLocationType":"INTERNAL_ID","dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"mods":{"dsLabel":null,"dsVersionID":"mods.5","dsCreateDate":"2016-12-08T17:49:50Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"M","dsSize":1931,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:cj82nq05k+mods+mods.5","dsLocationType":"INTERNAL_ID","dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"}},"objLabel":"NUNews.LI.21(Apr.10.1970).003.PantherSupporters.pdf","objOwnerId":"fedoraAdmin","objModels":["info:fedora/afmodel:CoreFile","info:fedora/fedora-system:FedoraObject-3.0"],"objCreateDate":"2016-10-05T15:54:24Z","objLastModDate":"2016-12-08T17:49:50Z","objDissIndexViewURL":"http://nb4676.neu.edu:8080/fedora/objects/neu%3Acj82nq05k/methods/fedora-system%3A3/viewMethodIndex","objItemIndexViewURL":"http://nb4676.neu.edu:8080/fedora/objects/neu%3Acj82nq05k/methods/fedora-system%3A3/viewItemIndex","objState":"A"}

northeastern:drs:repository:staff

northeastern:drs:library:archives

public

001614785

neu:cj82ng65k

neu:cj82ng65k

001614785

001614785

/downloads/neu:m040qh69p?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m040qh69p?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m040qh69p?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m040qh69p?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m040qh69p?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

/downloads/neu:m040qh69p?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m040qh69p?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m040qh69p?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m040qh69p?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m040qh69p?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

PdfFile

PdfFile

neu:cj82ng65k

001614785

/downloads/neu:m040qh69p?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m040qh69p?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m040qh69p?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m040qh69p?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m040qh69p?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

PdfFile

Panther supporters plan Seale rally

Panther supporters plan Seale rally

Panther supporters plan Seale rally

Panther supporters plan Seale rally

1970-04

1970-04

African American Students

Black Panthers

Political Activism

African American Students

Black Panthers

Political Activism

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20221220

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20221220

African American Students

Black Panthers

Political Activism

Panther supporters plan Seale rally

Panther supporters plan Seale rally

panther supporters plan seale rally

1970/04/01

Panther supporters plan Seale rally

1970-04

African American Students

info:fedora/afmodel:CoreFile

info:fedora/neu:cj82ng65k

Northeastern NEWS, April 10, 1970 Page 3 Panther supporters plan Seale rally By JIM KELLY The newly organized Black Panther Support Group, which has proclaimed April 14 as (CBobby Seale Day," is planning a demonstration to call attention to the upcoming trial of the party chairman. Seale, who fac s charges of murder and conspiracy to murder, is scheduled to enter his plea on Tuesday before a New Haven court. The agenda includes a rally in the quad, followed by a march to Post Office Square. There the marchers will assemble with other area Panther support ot·ganizations and listen to speeches by various New Left personalities. Proceeds from the exchange program would go to the Boston Pa:nthers, who are directing ef.. forts to provide Roxbury children with hot breakfasts. In addition, the National Committee to Com· bat Facism, a white radical or· ganization which Is also conduct· ing a hot breakfast program, in Cambridge, will be supplied. "It's a way for the Northeestem student to relate to a community which the university has exploit· ed," stated George Fleischner 73LA, a member of the coalition. Speakers will include Mrs. Seale, wife of the Panther leader, Charles Garry, Seale's defense at· torney, David Hilliard, Panther chief of staH, Adria Jones, di· rector of the party's Boston chapter, and Howard Zlnn, professor from Boston University. Boston College presently has a food exchange program similar to the c>ne being proposed here. Saga, the cafeteria service at BC, supplies the Mission Hill and Cambridge hot breakfast pro· grams with food. Dormitory students at that school finance the programs by sacrificing their breakfast once a week. After the speeches the demonstrators will proceed to the Berkely Street police station, where a second prc>test rally will be held. The Panther supporters are also -PatMartln encc>uraging dormitory students "THE. BREAKFAST PROGRAM in itself is revolutionary because it's to participate in a food strike. free/' nid a member of Boston's Black Panther Party at a teach-in Such a strike is designed to dramTuesday noon sponsored by Northeastern's Black Panther Support atize the group's proposal to imGroup. plement a food exchange program. Capitalist resigns to bureaucracy asserts Galbraith in DSS speech By KATHY KEPNER After congratulating the audience for their "good fortune" in having himself replace Senator Barry Goldwater (R-Ariz.) as the fourth guest in,. this yew's. Dis~ tinguished Speakers Series last Thursday, Harvard Prof. John Kenneth Galbraith explained and defended his theory of economics first expounded in his controversial book "The New Industrial State." According to Galbraith's hypothesis, which denies the neoclassic idea of consumer sovereignty and advances that of producer sovereignty, the growing complexity of technology has Moon man coming Former Astronaut Michael Collins, who flew the command module during the Apollo XI moon w.3.I.k, will speak at commencement exercises June 14, in Boston Garden. Earlier this year Collins was sworn in as Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs. In this capacity, he is responsible for State Department relations with the American public. In July, 1966, Collins also participated in the Gemini X space flight and became the nation's third space walker. Approximately 3,800 students will be graduated. . COL. MICHAEL COLLINS forced the "one man" behind the corporation to resign his power to the bureaucracy. "The rigid organization has taken over the decision-making power f mn the capitalist in modem industry," the former ambassador to India told the capacity audience. "The power bas been removed from the owners and put impersonally into the organization where the knowledgeable people are." Galbraith stated that the myth of the "corporation genius'' is a fallacy. "The genius who would know everything about an automobile would be rare. The true genius in modern technology is a combination of ordinary men of very specialized knowledge," he said. Galbraith pointed out that an individual genius could be suffering from a hang-over or taking a lunch break when an unexpected emergency arose. Therefore, he concluded, the committee system is much more "predictable and dependable!' Galbraith outlined four main roles for the modem state in industry. First, "if people can't afford beer or an auto they won't buy it," he said. "Therefore, the state must keep the purchasing power of the general public stable." Second, 11this is a system that requires very specialized, and skilled manpower, none of which industry can provide by itself. Therefore, it is the role of the state to aid monetarily very cost· ly modern technological proiects that are not purchased by the general public," the professor continued. Third, the state must help in education. And, finally, the government must stabilize public demands. According to Galbraith the cc>nsumer market is very unpredictable, especially in regards to technical products. Therefore, a "mass persuasion" campaign is necessary to control the public. "Also, necessary in controlling products and stable prices," said the public's demands are fixed Galbraith. Four outstanding criticisms have appeared over the past four years of Galbraith'-s sovereignty of the producer economic theory according to the economist. The first states that Galbraith is merely speaking of the world of the "great corporation" and that in reality there is another world composed of farmers and that this world is still subiect to the market. According to these critics it is here the consumer sovereignty still holds. In rebuttal, Galbraith said, ''I agree, but still large coporations account for half of all economic activity and this is the part of society that has the greatest change." The second criticism attacks Galbraith's methodology. "They say economics should be established through small provable points and that the economist must determine the little things. But, little things must be examined in larger areas, which is consumer sovereignty," he said. Galbraith said he thought this argument is asserted by the conservatives as an attempt to avoid the real question. A petition, calling for immed· iate initiation of the program, is currently being circulated in the dormitories. Furthermore a motion supporting the proposal has already been introduced to the Student Counci I. If successful, both will be presented to the administration and Wilbur's Food Service next week. Plans for the future include both a clothing drive and a campaign for funds and supplies for a Roxbury medical clinic. Fleischner commented that "the reason that we have set up is to serve the people. This is the first time,'' he continued, "that a radical organization has served a comm u n i t y c>f both blacks and whites." The main reason for the existence of the Panther Support, according t() Fleiscbner, is "to educate people about the Panthers. The fear of the Panthers," he continued, "arises out of ignc>rance. The biggest myth we would like to explode is the picture of a black-jacketed, headhunting Panther marching up the streets shooting up middle class whites." r;::::::;:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::I::::::::::H:III.I::::::n:::::::::c::::tj I d II H SDS m.eiDhers arrested :: By JIM KELLY is located, when they observed Four SDS members, two of them from Northeastern's Cienfuegos were arrested Tuesday near English High School. Police charged Bert Weiss 73LA, Richard Ferguson 74LA, David T. Sloane, a student at BU and Terrence O'Grady, formerly of BU, with attempted breaking and entering, and defacing of city prop- four men near the institutic>n's erty. Judge Samuel Eisenstadt of the Roxbury District Court ordered that the four be held for a hearing April 16. They were released on $1500 bail. Officer Vincent Logan of District 10 claimed that he recovered a pinch bar, a number of leaflets, and a iar of glue at the front door of English High. He further stated that the door had been forced open with the pinch bar but that entrance had not been obtained. Police officials stated that P.atrolmen Murphy and McGrath, both of District 10, were driving along Louis Pasteur Avenue, the street on which the high school entrance. The four allegedly fled in an automobile when the policemen tried to question them. Murphy said that he radioed headquarters, summc>ning Patrolman Logan, who repc>rtedly forced the car to the curb of Brookline Avenue, which lies parallel to Avenue Louis Pasteur. The pc>lice report further stated that Weiss received facial injuries in an escape attempt while he was being phc>tographed and fingerprinted at Berkely Street Police headquarters. Officer Logan claimed that Weiss broke loose and ran for the exit, which is located on the third floor. Logan said that in his ensuing attempt to apprehend Weiss, both tumbled down a flight of stairs. Weiss was allegedly iniured from this fall and was taken to Boston City Hospital where he was tr..ted for a swol· len eye, lacerations above the eye and lip, and a possible broken nose. Patrolman Logan apparently sustained no lniuries. Third critics say that "one can't p~ove that this persuasion, that the consumer is subjected to, is effective," said Galbraith. "People deny being influenced by commercials and therefore believe no one else is influenced either." "Fourth, is the general attack from the left who says that the whole argument which puts power into the organizations is a slight-of-hand in which reactionaries take the power from the big capitalist," he said. The leftists must ultimately conceive that the power in the modern economic society and state cannot lie with individuals but must lie in the bureaucracy for they see the USSR is merely changing one bureaucracy for another. i I . JOHN KENNETH GALBRAITH �

2016-12-08T17:49:59.03Z

2016-12-08T17:10:16Z

A

CoreFile

neu:cj82nq06v

{"datastreams":{"RELS-EXT":{"dsLabel":"Fedora Object-to-Object Relationship Metadata","dsVersionID":"RELS-EXT.1","dsCreateDate":"2016-10-05T15:57:26Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"application/rdf+xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"X","dsSize":425,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:cj82nq06v+RELS-EXT+RELS-EXT.1","dsLocationType":null,"dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"rightsMetadata":{"dsLabel":null,"dsVersionID":"rightsMetadata.4","dsCreateDate":"2016-12-08T17:10:16Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"M","dsSize":687,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:cj82nq06v+rightsMetadata+rightsMetadata.4","dsLocationType":"INTERNAL_ID","dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"DC":{"dsLabel":"Dublin Core Record for this object","dsVersionID":"DC.5","dsCreateDate":"2016-12-08T17:10:16Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":"http://www.openarchives.org/OAI/2.0/oai_dc/","dsControlGroup":"X","dsSize":719,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:cj82nq06v+DC+DC.5","dsLocationType":null,"dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"properties":{"dsLabel":null,"dsVersionID":"properties.5","dsCreateDate":"2016-10-05T16:01:20Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"M","dsSize":718,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:cj82nq06v+properties+properties.5","dsLocationType":"INTERNAL_ID","dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"},"mods":{"dsLabel":null,"dsVersionID":"mods.4","dsCreateDate":"2016-12-08T17:10:16Z","dsState":"A","dsMIME":"text/xml","dsFormatURI":null,"dsControlGroup":"M","dsSize":1919,"dsVersionable":true,"dsInfoType":null,"dsLocation":"neu:cj82nq06v+mods+mods.4","dsLocationType":"INTERNAL_ID","dsChecksumType":"DISABLED","dsChecksum":"none"}},"objLabel":"NUNews.LI.22(Apr.17.1970).Protest.pdf","objOwnerId":"fedoraAdmin","objModels":["info:fedora/afmodel:CoreFile","info:fedora/fedora-system:FedoraObject-3.0"],"objCreateDate":"2016-10-05T15:57:22Z","objLastModDate":"2016-12-08T17:10:16Z","objDissIndexViewURL":"http://nb4676.neu.edu:8080/fedora/objects/neu%3Acj82nq06v/methods/fedora-system%3A3/viewMethodIndex","objItemIndexViewURL":"http://nb4676.neu.edu:8080/fedora/objects/neu%3Acj82nq06v/methods/fedora-system%3A3/viewItemIndex","objState":"A"}

northeastern:drs:repository:staff

northeastern:drs:library:archives

public

001614785

neu:cj82ng65k

neu:cj82ng65k

001614785

001614785

/downloads/neu:m040qh87m?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m040qh87m?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m040qh87m?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m040qh87m?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m040qh87m?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

/downloads/neu:m040qh87m?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m040qh87m?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m040qh87m?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m040qh87m?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m040qh87m?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

PdfFile

PdfFile

neu:cj82ng65k

001614785

/downloads/neu:m040qh87m?datastream_id=thumbnail_1

/downloads/neu:m040qh87m?datastream_id=thumbnail_2

/downloads/neu:m040qh87m?datastream_id=thumbnail_3

/downloads/neu:m040qh87m?datastream_id=thumbnail_4

/downloads/neu:m040qh87m?datastream_id=thumbnail_5

PdfFile

2000 Protest Panther Trial

2000 Protest Panther Trial

2000 Protest Panther Trial

2000 Protest Panther Trial

1970

1970

African American Students

Black Panthers

Political Activism

African American Students

Black Panthers

Political Activism

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20221225

http://hdl.handle.net/2047/D20221225

African American Students

Black Panthers

Political Activism

2000 Protest Panther Trial

2000 Protest Panther Trial

2000 protest panther trial

1970/01/01

2000 Protest Panther Trial

1970

African American Students

info:fedora/afmodel:CoreFile

info:fedora/neu:cj82ng65k

Northeastern NEWS, April 17, 1970 Pf~Ge 3 Factionalized mass mars moratorium By NANCY BURTON Factionalism, polarization, power to the people, love, Bobby Seale, grass, racism, Abbie Hoffman, and eventually war were the themes focused on in shifting surges at Wednesday's Moratorium in the Common. In a turnout at least as large lieves they have restored a ''beas that of last October's demon- lief in the dignity of man and stration, the predominantly equality and iustice before law.'' young crowd ~pressed a de- But he quickly turned to the mand for immediate withdrawal problem of erasing differing of all U. S. troops from South- ideologi" and programs in order east Asia. to reach mutual go Is. But in the succession of events, He expressed the belief that the seemingly unifying demand "we don't have much time left" could not catalyze solidarity and predicted that "within a year either on the part of the dem- America either will have achieved onstrators or the speakers. freedom or fascism." He ended By the time the Northeastern with a call for solidarity: "Let's contingent of 1500 arrived at · walk this last mile together." 3 p.m., diHerent factions could Worth introduced James Shea, be identified on the Common. state representative from NewThese included day.glo-painted ton, to the assemblage. Shea Yippies, high school activists, alluded to the "troubled waters" Black Panthers, and members of and "growing restlessness in this the November Action Coalition. country." He discussed the "spiralling of Preliminary entertainment was repressive measures" being instiprovided by an assemblage of tuted across the nation and in flute, guitar, and tambourine- particular the concept of presportin~ members .of Boston's ventive detention, which he said cast of "Hair'' and folksinger was aimed at those who "in the Jaimie Brocket, as the various future might commit crimes." he school contingents arrived. foresaw a solution to the "costly A telegram message addressed misadventure in Southeast Asia" to Boston Moratorium people when "shrewdly and aggressivefrom London was read: "Love ly imaginative measures have to you all/Love now and peace been taken by the people to com· will follow/Love, John Lennon." pel it to end." Settling into the business at Further, he predicted that Nov· hand, a black minister hailed ember's national and state alec· "All power to the people!" and tions will oHer the opportunity began with an invocation appeal- to choose representives with ing for peace and brotherhood. "guts and intellect'' and that Prof. Steve Worth, of the change will be best effected Northeastern political science de- through this procedure. partment, gave the keynote adCarol Lipman, national execudress. He began by offering a tive secretary of SMC, was in· debt of gratitude to "the young terrupted from speaking by Progeneratio in- general'' for he be- gressive Labor groups who 2000 protest Panther trial By BRUCE SHLAGER Chants of "Free Bobby, free Ericka, power to the people" echoed through the streets· of downtown Boston Tuesday afternoon as 2000 persons protested the New Haven murder and conspiracy trials of Bobby Seale, chairman of the Bl~ck Panther Party, Ericka Huggins, and twelve others. The Panthers and their supporters say the trial is a frameup; an attempt by the government to suppress the revolution. A contingent of about 70 Northeastern students, led by members of the Panthers, had earlier marched from the quadrangle to Post OHice Square, the first rallying point of the city-wide protest. They curied flags reading " Free the Panther~', and " chanted revolutionary slogans. At the Post Office Square rally Doug Nfiranda, fonner chairman of the Black Panther Party in Boston, chided the white activists present for being too hung up on ideology and abstractions. The black community, he said, "is tired of white activists arguing over who's a male chauvinist, who a revisionist, who's this, and who's that. We want less talk and more revolutionary action." When the battle's in the streets," Miranda continued, "we got to know who's dealing with the oppressors and who isn't; who's fighting and who isn't; who's on acid and who's there cleaning out the gun." Mrs. Artie Seale, wife of the jailed Panther leader, also urged whites to take action. She spoke of the importance of what happens in New Haven. "The black community and other .oppressed communities all have their eyes on New Haven, and we'll be damned if they give them the electric chair," she told the crowd. Following Mrs. Seale's speech, the demonstrators, led by women, marched up Milk Street, onto Tremont, Boylston, and St. James streets to Boston Police Headquarters on Berkley Street. Chants of "Free the Panthers, free ourselve~' rang through the narrow streets. Members of Boston's Tactical Police force lined the march roufe. "ll1to the streets, onto the jails, people's power if Panthers fail," yelled the protesters as they paraded down Tremont Street. (Continued on Page 13) threatened the order of the demonstration for much of the remainder of the afternoon. The chairman of the Massachusetts Welfare Rights Organization, Mrs. Wilson, called for a program of ubread and justice" as a peace symbol was being designed directly overhead by a low-flying plane. She decried the present system for harboring "welfare for the wealthy, ill fare for the poor." The tightly-packed crowd, which had been alternately standing and sitting cross-legged, was mostly upright after Doug Miranda, representative for the Black Panthers, began to speak. He degraded the Moratorium itself as a "futile demonstration'' (Continued on Page 13) -lean Paul Cayre FOR THE SECOND time in less than a year, approximately 100,000 merged onto Boston Common Wednesday, raised their hands in a peace sign, and demanded immediate withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam and an end to the war. 'Ready to rock cradle of liberty?' By EDWARD O'DONOGHUE Street revolution - the bloody arm of th young resurrected from years of American history classes. Once it belonged to true patriots, now, reportedly, the possession of traitors, social deviants, and under privileged troublemakers. Only in America can one announce a Harvard Square takeover, days in advance, and still be allowed to "Do it!" From the Moratorium came an army of New Left factions groups that made the Moratorium a day of factional speakers ad· dressing each one's faction. But from this came a mass to march through Cambridge and seize the kingdom of Johft Harvard, Longfellow, 01i¥er Wendell Holmes. Four newsmen arrived at City Hall in Cambridge, 30 minutes before the legions. Fifty tactical policemen stood ready on the sidewalk before the structure, more were rationed out across the street. They were armed with the usual equipment: steel helmets; the long, thin, heavy batons; heavy coats and badges that were soon to disappear. The K-9 corps was also represented by a leashed German Shepard, amiable enough for picture-taking sessions. Sunset to the west, a blue flashing light to the east, and a group of approximately 200 people, mostly black, marching from the south. Was this all? a few cries of "Off the pig! Kill the pig!" Was this all? The police standing shoulder to shoulder, sticks held horizontal as the group of youths - mostly too young for college - move by. The road leads to Harvard Square. Was this all to march on Harvard Square? It was the first time during the evening when the sens• of uneasiness bec•use of inactivity perpertrated the ,atmosphere. Down Massachusetts Avenue came the armies of the evening. The police fingered their batons, the crowds advanced, the forerunners of the mass were passing City Hall throwing their barbs of "Off the pigs-Kill the pigs." One marcher was dragged up the stairs, the lines were now passing-the taunts grew louder and a sound truck blared ••don't stop," the main action isn't here and there is no reason to break up the group over City Hall The battalion moved faster. the line was falling apart. The people in the rear were trying to catch up. Past the rubble of old bui Idings it progressed. Rocks were picked up from th vacant lots--"Free Bobby Seale"- One, two, three, four-We don't want your fucking war." People were breaking the ranks to find the perfect rock. Peace preservers were yelling to drop the stones-"What the fuck are you doing? No one's gonna get hurt if you don't start something. What the fuck are you doing?" People were breaking rank. The rocks were being picked up. The rearguard was trying to catch up. The front ranks finally heeded the cries of the rear guard. At Putnam Squar• the front halted. The marchers closed up. On could see the mass was not totally students. A blind man was being led by two girls, several people were on crutches, an amputee came by Oft crutches. Older citi· zens were there~ and other older cltbens lined the windows and stood at bus stops watching and murmuring and avoiding direct contact with tiM marchers. The Old Cambridge Baptist Church was readied for use as a hospital. A young doctor yelled that if anyone was hurt, medics would be there. Red Cross banners on the structure, Bobbie Seale banners in the street. Radicals called to the medics to forget the hospital and join the street people. AJ; the mass resumed motion, the square opened up ahead. Out of the walls on the right, or the street on the right, or the air all around came the nasal ". . . And the times they are achanging" of Bob Dylan's preBerkley song left over from days of nonviolent protest marches. The square opened up. Linden Street - The concrete and glass highrise Holyoke Center, a structural composite of small shops and Harvard offices lies to the lflt of Massachusetts Avenue. The colorful window displays looked on the first half of the march. The later street people broke the reflective si· lence of the ~ter. Bricks_. rocks, glass shattered, Cambridge Trust opened up to the street air, out(Continued on Page 9) -Alan Wudemu CONFRONTATION IN CAMBRIDGE-Police and demonstrators battled in Harvard Square Wednesday night following the Moratorium activities on Boston Common. Approximately 200 demon~rators and 17 police oHicers were iniured during the melee. �Northeastern NEWS, April 17, 1970 Page 13 Zinn: 'America's a police state' (Continued from Page 3) moved out from inside headquarters, and faced the crowd. There were no further incidents at the ...Join us, join qs,•• they urged by. rally. Zinn, the closing speaker at When the demonstrators ar.ved at police headquarters they in front of the the rally, declared, "America has been a police state for a long time." Referring to the city hospital shooting death of Franklin Lynch, a black man, by a white patrolman, Zinn stared directly at the police assembled on the sidewalk, and asked, "How can any of you defend an act of murder against a man in a hospital?" After Zinn spoke, the demonstrators left the are~ heading back down Berkley Street, up Commonwealth Avenue to BU. As the demonstrators passed through Kenmore Square several of them threw rocks at the National Cash Register Company and the First National Bank, breaking a number' of windows. building~ tiDg CCOff the pig!)) A number of plainclothesmen mingled among the crowd while others, holding radios, watched the windows of surrounding buildings. Uniformed members of the TPF, remaining just out of · t of the demonstrators, had the area surrounded. Two members of Boston•s Puerto Rican community were the first to address the gathering. They spoke of the struggle for independence going on in erto Rieo and its common cause with the Black Panther Party. Also speakiDg in front of po. headquarters were Doug Mirda and Boston University pro- At BU's Shennan Union the march enclecl, and the .,-rtlcl· pants dispersed, promising to work to build a bl..,.r base for a continued struggle. Twelve squad cars ..nd two busloads of pollee followed the marchers up Commonwealth Avenue to the end of the march route.· fessor Howard Zinn. Shortly after Miranda's t.lk a almost succeeded In INiullng down the American , ... fly1 in front of the building. As plalnclothellnen sebec~ the youth nd placed him under arrest, the crowd su..... forward, protesting. Fifteen policemen wearing helmets and wielding nightsticks A short time later, at approximately six p.m., a acuffle broke - --·-· ..::i! -=····::::-.:::::····-··-···::::::::::.::::::~• ~i Dartmouth ·College i :: g COEDUCATIONAL SUMMER TERM ~UNE u :i ii :! 28 - AUGUST 22 Liberal Arts I H :: f: Undergraduate credit courses in human· ; iti s, sci nces, social sciences - intensive I reign language instruction - introduc1 tory computer course I I I I I ro receive Summer rerm Bulletin write to: ~ i! tl i I .I SUMMER PROGRAMS OFFICE A crowd of several hundred, some of whom had partfcfpat.d in the earlier demonstration, formed as the patrolman, lolned by • coli gue, chased the youth a short way down Commonwealth Avenue and appr hended him In front of Grahm Junior Colleoe. As the two policemen were dragging him into the patrol wagon, dozens of police, some wielding night sticks, converged on the area, pushing the protesting crowd which had witnessed the urest onto the ,ldewalks. Five minutes later all was calm. Police left the area, leaving an angry and bewildered crowd behind. Friends of the arrested youths then collected money for bail. PARKHURST HALL (Continued from Page 3) that "wouldn't get us out of the war." Calling for an end to "social pacifism," he urged all young people to "pick up guna," con· tlnulng thet the . c.ll no longer "OH the pig" but rather "Death to the pig/' He answered with shouts of "Peace! Peece nowl" and two..flnger peace gestures. w• w• Eighty-three-year-old Florence Luscomb, wbo attesta to having been in the women's liberation movement for 70 years, followed Miranda to the podium and related the struggle of Vietnamese peasant women to that of women all over the world. But her speech was abruptly cut off when the PL people, who had just arrived from a demonstration at City Hall. demanded equal time for their own spokesman. Then Abbie Hoffman toot the microphone 1b cheers of support and acclaim, remarking, "Boston's a goddam faction center!" He DON'T SCRAMBLE I g = England Deaconess Hospital Blood Bank c.ll 734-7GOO, Ext. 551 or 559 for .-..,.a~ta~hMint be 21 n or older. $25 AU IT After abe had left the platform, charismatic Hoffman immediately compelled renewed audience-wide enthusiasm: •"Boston is the center of disillusionment and frustration. Too goddam many professors and universities aDd stainl steel cucteroost" He mentioned tiNit It wu •gooc~ to be home,'' being a naflve of Boston, but ............. the changIng" lanclscape, pointing to NOesolatlon Ror' ln et wu formerly Scollay Square, and the construction of the John Hancock Building near the Pru. John Hancock a revolutionary, not a fucking life Insurance sal ,• he scr.mecl. He reealled April 18. 1T75 in Assuming a more subdued air, Hoffman said that "the Bobby Seale trial is more important than ours," referring to the recent Chicago 7 trial in which he was one of the defendants. He called for support against the war, racis~ and Bobby Seale and the of the jailed Panthen. He cl-.d with a call to action.: "Boston-the cradle of llb..-ty. Well, 1101ne cradles INve to a.. rocked. Who's ready to rock e cradle? Who's ready to cradle a roclc?"' Kelly, Socialist Workers f1uty candidate for governor of husetts followed Hoffman, as did .John Corey, a Vietnam v~ student from South Vietnam, and a spokesman from the Puerto Rican student Federation. '!be activities of the Commons were concluded with a final presentation by the cast of •'Hair:' for an A.,-rtment CALL 536-0730 or ... us at 906 Beacon Street LEO HIRSH, I C. Going Out Of Business SA Aflf1.Y AT You mass movement. d.ifierent terms: Paul Revere catclring sight of the strobe light and racing on his motorcycle calling, "The pigs are coming! The pigs are coming! Bring out the revolution!" .::::::::::::::=! BLOOD DO ORS EEDED ew was reprimanding the PL group in particular, telling them to "Sit down, damn youl" but at this point Fran Weindling, a spokeswoman for Progressive Labor, was given time to speak. She, in effect, labeled the proposals and speeches of all who bad spoken before her a "farce" and ealled for an alliance with "the workers" to create a militant S & S REALTY h11 ewer 100 for Singles •nd Groups fi Box 582 HANOVER, NEW HAMPSHIRE 03755 YOUTH AGAINST WAR AND FASCISM marc::h bv th Common on their way to Station Four to pro the imprisonment of Bobby Seale. Bread, justice, and end of ·pacifism I P. ""::::: out near Kenmore Square hen a policeman jumped out of a patrol car parked by the center strip of Commonwealth Avenue and ran towards a youth holding a purple flag which read "Free the Panthers." E ENTIRE STOCK SUITS, SPO T COATS Now Cut to 1 12 Original Price ONCE IN A LIFETIME SAVINGS ON RAINCOATS, SWEATERS, SLACKS, SHI TS, NECKWEAR, ACCESSO IES, FORMAL WEAR, etc. Bankam ricard, Master Charge, and UniQrd Accepted LEO lllRSH, Inc. 250 HUNTINGTON A VENUE (opp. Symphony HaiQ need a better tomorrow. Help us - in lifting man ... even high enough to touch God. The Trinitarians Garrison, Maryland 21055 I sought my Soul, but my soul I couldn't I sought my Gotl but my God elutletl me. �

2016-12-08T17:10:25.757Z